embracing the light

on marthas road, an atrium lies at the heart of an art-filled home

by stephen brookes • photography by chris mcnamara

Is there anything less exciting than the entry path to a house? It’s not there for the glamour, that’s for sure — its job is just to get you (or your Amazon delivery) to the front door with as little fuss as possible. Some are pleasing enough, prettied up with flowers and maybe a flirtatious little curve. But a good entry path just kind of … lies there, happy to be ignored, a self-effacing handmaiden to the front door itself.

architect: luis vera

date built: 1959

levels: two

bedrooms: three

size: 1,938 square feet

lot: .42 acres

addition: michael cook

But stroll down Marthas Road, and you’ll find what may be the most self-confident entry path in all of Hollin Hills. It’s a playful, almost sculptural thing: a boardwalk made of layered geometric shapes that seem to turn gently this way and that, echoing the clean lines of the house while asserting its own individuality.

And as it draws you toward the house, you realize that the boardwalk is also a kind of bridge — tying a spiky modernist garden on the left to a serene Japanese rock garden (complete with lichen-covered boulder) on the right. It’s a striking effect, and seems to unify two very different cultures into a new and unexpected whole — while letting you know that you’re in a place where things may be a little … out of the ordinary.

A geometric boardwalk ties sun-drenched modernism on one side, with cool Japanese serenity on the other.

For you’ve arrived at one of the most intriguing houses in Hollin Hills, a home that explores the connections between diverse and often wildly contrasting ideas. With its flat roof, rectilinear lines, open-plan layout and vast walls of glass, it fits seamlessly into the modernist style of Hollin Hills architect Charles Goodman. But it’s not a Goodman home — it was designed in 1959 by a Chilean architect named Luis Vera, who lived here with his family for about six years.

And Vera used the house to test what was, at the time, a radical new idea: that designing a house around a central atrium would both connect and separate its public and private areas, and unify the different “zones” of a house into a more satisfying, integrated whole.

The experiment was a success, and the Vera house has become a place where a global range of cultures and ideas — from tribal artifacts to modernist paintings, pre-Columbian pottery to ceramics from Hollin Hills artisans — all come together in harmony. It’s a setting for imaginative living, and reflects the creativity of its owners of the past thirty years: a renowned geophysicist and his wife, an equally accomplished textile historian.

The view of the atrium from the entry, with the living area to the right.

into the light

“Please come in!” says the historian, opening the front door to a visitor. A tsunami of autumn light suddenly washes over us, pouring through a wide, glassed-in atrium that faces the front door.

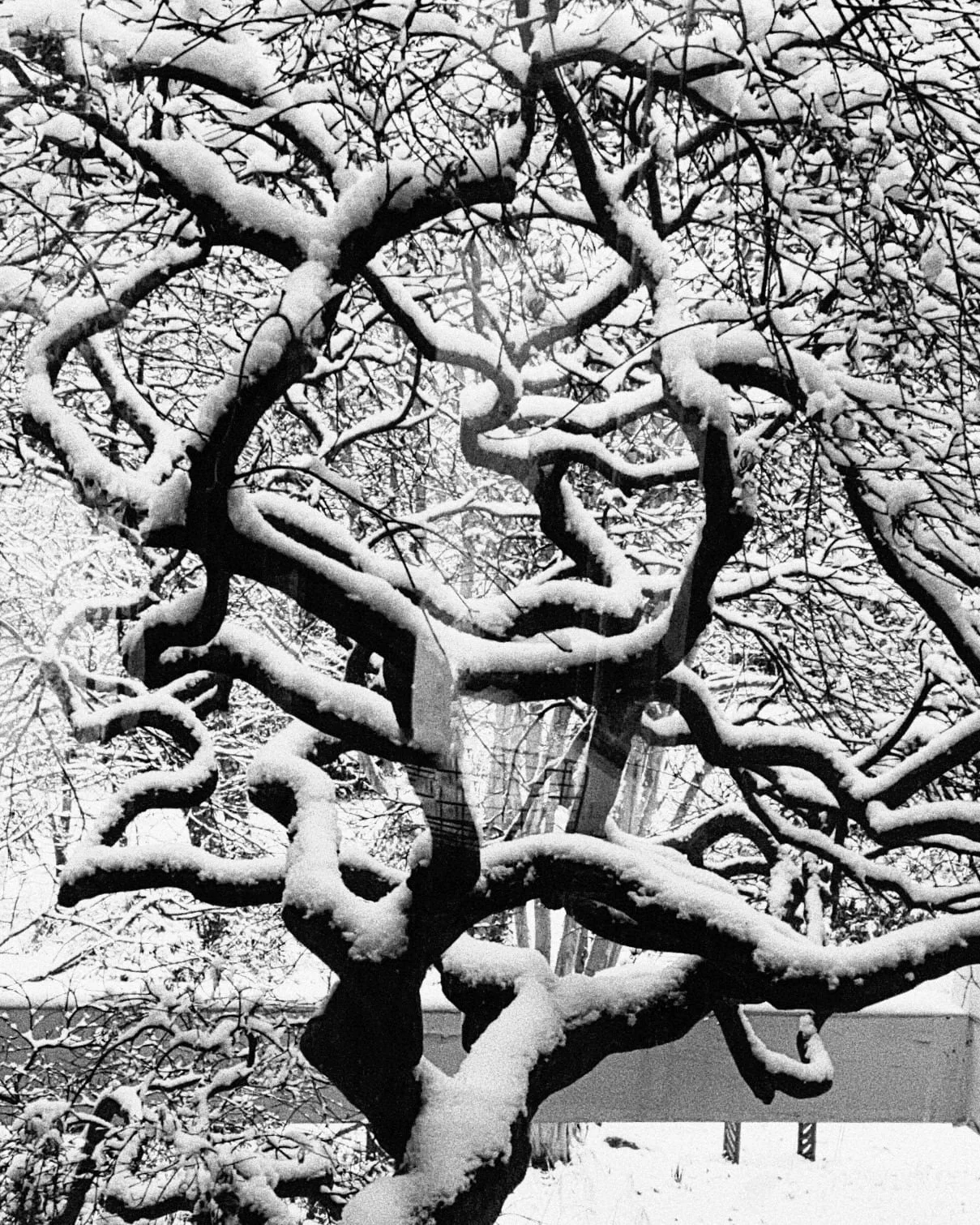

And framed inside the atrium — as if in an enormous jewel case — is a graceful, decades-old Japanese Maple with a filigree of delicate golden leaves on its branches. Growing from a bed of gravel with two small boulders at its side, it’s elegant, serene, even poetic — a piece of sculpture as much as a living thing. The effect is so striking that it almost stops you in your tracks.

“This,” says the historian, as she gazes almost fondly into the sunlit tree, “is why we chose this house.”

There may, in fact, be no more uplifting way to enter a home. The atrium seems to effortlessly erase the line between nature and architecture, and with the rest of the home wrapped around it on either side — public spaces to the right, private spaces to the left — it feels like the living, beating heart of the house. The maple’s intricate branches and colorful leaves provide an always-changing counterpoint to the atrium’s crisp geometric lines, and its quiet charm, say the owners, is one of the home’s deepest pleasures.

“There’s never a wrong season to see this tree,” says the owner. “It’s always beautiful.”

the binuclear home

The strategy of using an atrium to both connect and separate two different wings of a home originated with one of the most important designers of the modernist period, the Hungarian-American architect Marcel Breuer.

Clockwise from top: The atrium of the Vera house in 1959; sunlight casts a filigree of shadows on the floor; a Chiwara headdress echos the maple’s curves; the tree shows different personalities as the seasons change, and is especially dramatic in the winter.

“Luis Vera’s layout of this house was influenced by Breuer,” says the geophysicist, as we pass from one wing of the house to the other. It’s not known if Vera (an architect and urban planner for the World Bank, who worked on the city plans for Bogota, Chandigarh, Ixtapa and other major projects) actually met the Hungarian designer, who is perhaps best known for his design of the original Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. But Breuer’s pioneering “binuclear” approach was widely discussed in the postwar years, and it’s clearly the inspiration for Vera’s design.

At the heart of Breuer’s thinking was the idea that architecture could, and should, unite a range of opposing ideas: private with public, light with dark, traditional with modern. “The real impact of any work,” he wrote in his 1956 monograph Sun and Shadow, “is the extent to which it unifies contrasting notions — the opposite points of view. I mean unifies, and not compromises.”

The west-facing living area features vintage Danish chairs by Peter Hvidt and Finn Juhl, an Arne Hovmand-Olsen coffee table, an African mask from the Ngil people, and a copper fireplace surround made by the owners themselves.

Marcel Breuer: going binuclear on modernist architecture.

left brain, right brain

And that unifying ideal is at the heart of the Vera house, whose “binuclear” design may be unique in Hollin Hills. The private wing of the house, for instance, is not only where the owners sleep; it’s where they have their creative workspaces. The historian kept her loom in a room overlooking a magnificent Yoshino cherry tree in the back, while the geophysicist works from an office downstairs. Both spaces are, shall we say, enthusiastically lived in, full of books, desks, papers, more books, more papers, and an easy informality of every kind.

“Of course it’s messy,” says the scientist, with a grin. “This is where we live!”

It may be too much to draw a left-brain/right-brain analogy with the binuclear house, with the atrium as an architectural corpus callosum between the creative and the analytical sides of the home.

But leave the private area and walk past the atrium to the “public” wing of the home, and you’ll find a much different space: open, calm and well-ordered. Floor-to-ceiling windows fill the living areas with light, bringing to life a collection of art that seems to span both the globe and the centuries. Breuer’s sense of “unifying contrasting notions” seems particularly vivid here, as delicate teak furniture mixes comfortably with the rough, dramatic shapes of African masks and ethnographic art.

a world of art

The eclectic collection reflects the open, adventurous personalities of the owners themselves. During a lifetime of travel they’ve brought home delicate graphite rubbings from Lima, shadow puppets from Jakarta, and aboriginal textiles from Alice Springs. There’s art they’ve created themselves (“that’s my ‘Rothko’, says the scientist, pointing to a door he painted with soft-edged rectangles of color), and works by friends and family, including striking assemblages made by the scientist’s mother, a professional artist.

Other works, meanwhile, have been passed down from earlier generations, connecting with the past.

“My father collected indigenous and tribal art,” says the historian. “African art, Oceanic art from the Pacific Islands, pre-Columbian art, art from the peoples of the Pacific Northwest.” It now brings drama and exotic textures to the house, from the Ngil mask over the fireplace to an intricately-carved Chiwara headdress from Mali set in a window by the atrium, where it echos the curving branches of the Japanese Maple.

A row of tribal masks, including (foreground) a dramatic carving from the Northwest Pacific Coast and two smaller masks from Western and Central Africa.

And throughout the house, the ethnographic and the contemporary art are woven together with a playful, try-anything spirit.

Take, for instance, those three life-sized, brightly-colored arms that reach out from a high wall. Nothing could be less “tribal” — they’re industrial molds used for making gloves. Or the bronze Paolo Soleri bell acquired during a visit to Soleri’s visionary, futuristic Arcosanti project — worlds away from any ancient society. Ferocious tribal masks hang comfortably near a dramatic “soft painting” by Calman Shemi, while handmade plates from Hollin Hills potter Susan Cohen sit naturally on a vintage teak dining table by the Danish designer Hans Wegner.

The old and the new, the serious and the whimsical, the local and the distant all seem to connect in a kind of conversation between profoundly different cultures — and bring the home vividly to life.

Above left: A detail from an assemblage by the mother of one of the owners. Right: Marley Bear, one of the couple’s cats, admires a Danish coffee table designed by Arne Hovmand-Olsen.

Repurposed as sculpture, industrial glove molds (above right) reach out from over a doorway, while handmade tiles (left) attest to the owners’ love of cats.

astronaut cows and their interesting satellites

The sleek, sophisticated lines of Danish Modern furniture have always fit naturally into modernist homes, and the couple’s enviable collection of vintage pieces (most of it bought by the historian’s parents in Copenhagen in the late 1950s) acts as a kind of bridge between the art collection and the architecture itself.

Take, for instance, the way the way the Nordic cool of a Danish teak sideboard anchors the tropical warmth of Vacas Astronautas, a playful, richly-textured print on handmade paper by the Mexican artist Teódulo Rómulo.

The print, with its astronautical cows jumping over the moon, has all the hey-diddle-diddle surrealism of the nursery rhyme that inspired it. And it’s drawn a curious array of art into its orbit; two Indonesian shadow puppets mimic the ascending cows, an Oceanic tribal figure reflects the color palette, and a boldly-patterned textile from the Congo amps up the vertical motion of the scene. A traditional Chinese “opera doll”, meanwhile, is joining the cows in flight, while a multicolored Uzbek cap on the sideboard rounds out the tableau, because … well, multicolored Uzbek caps need no explanation in a world where cows can fly.

A 1958 Danish teak sideboard by Peter Hvidt and Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen anchors a mixografia print titled “Vacas Astronautas” by the Mexican artist Teódulo Rómulo.

a vase, an imaginary view, and a beautiful daughter

“Let me show you something you might find interesting,” says the geophysicist, unfurling a crinkled roll of architectural drawings over the dining room table. There are half a dozen renderings of the house from 1959, all beautifully drawn — although one of them has the living room looking out to the west, toward … the Washington Monument and the Capitol?

“We think these were drawn by Luis Vera’s students,” he says, laughing. “They may have gotten one or two of the details wrong.”

The Luis Vera house in a 1959 rendering, including a patio and water feature that were never built. (Click image to enlarge.)

Imaginary views aside, the drawings show the original house from the western side, including plans — never realized — for a patio and fountain, which seems to include a waterfall from the atrium. The drawings show the original louvered wooden sunbreak that ran the length of the house (it was difficult to maintain, and eventually removed), and an open carport, about 20 feet wide, that ran under the southern wing of the house and gave the house a “floating” look.

Vera lived here until 1965, when he built a similar house for himself in Washington, DC. In the 1970s, a later owner bricked in the carport, creating a downstairs space which now serves as an office. But the change is said to have dismayed Hollin Hills children, who used to sled in the winter from Marthas Road, down through the open carport, and all the way to the bottom of Rebecca Drive.

The house particularly impressed a Hollin Hills child named Michael Sorkin, who would grow up to become one of the most respected architectural critics in the country. Writing decades later, he described the Vera home as “a simple house … which gracefully bridged its carport and which had a glazed entry through which the distant Blue Ridge could be seen.

“I remember the beautiful green vase that stood by the window,” Sorkin added. “And especially remember a beautiful daughter.”

Above: The Vera house from the west, in 1959. Note the open carport to the right, which was bricked in during the 1970s, and the original louvered sun break, since removed. Below: the house in 2025.

the architects are talking

Aside from the closed-in carport, the house hasn’t changed much since those early days. There’s a new wrap-around deck along one side, and earlier this year the owners decided they’d had enough of the black ceramic tiles in one of the bathrooms, and overhauled it completely.

But a more significant alteration took place in 2019, when the couple (both enthusiastic cooks) replaced the original galley kitchen with a spacious new addition designed and built by architect Michael Cook. The new kitchen expanded the house and gave it an L-shaped footprint, maintaining its sleek, light lines while adding imaginative architectural touches — done so deftly that they blend almost imperceptibly with the original home.

The addition is cantilevered slightly above grade, for instance, which gives it a subtle “floating” feeling, and two of the windows come together to form an almost-invisible glass corner, in a way that echoes the atrium. That’s a nod, says Cook, to the modernist architect Richard Neutra, who liked to “remove” corners to blur the line between inside and outside.

“Sometimes we reference Charles Goodman in our Hollin Hills work, and at other times we want to be a little more provocative,” explains the architect, who’s designed multiple additions and renovations in the community.

“I like to use ideas from other architects of that period,” he adds. “But we’re subtle about the alterations, and keep everything within the modernist vocabulary.

“It’s a success,” he adds (maybe channelling Marcel Breuer for a moment) “if people can’t see the delineation between what is old, and what is new.”

Designed in subdued, sophisticated tones with white countertops and pale wood cabinets, the kitchen has open shelves to display the couple’s art pottery, and looks out onto Marthas Road.

At the transition into the kitchen (above left), a clerestory window houses a colorful collection of glassware, over paintings by the homeowner’s mother, and a handmade chair. Two of the street-facing windows come together in an “invisible” glass corner (above right), a nod to the midcentury architect Richard Neutra.

the sea at the top of the hill

Outside, meanwhile, the afternoon sun is deepening, casting a luminous glow through the house and filling the windows by the front door with light. By the entry, an enormous miscanthus sways gently in the breeze; further down the path a crisp, geometric triangle of yuccas catches the sun, while a crepe myrtle quietly drops its leaves over the Japanese garden. Like the house itself, the landscape seems to encompass two distinct and distant worlds, bound together in conversation.

Above: Sunlight streams through the Vera house. The contrasting color scheme — “Bauhaus Beige” on the original house to the left, a darker “Sarsaparilla” on the 2019 addition to the right — is meant to maintain the individuality of each section. A mass plantings of yuccas (below) creates a modern look.

“It’s a fascinating design,” says landscape architect Dennis Carmichael, admiring the scene.

“You have a sun garden — almost a ‘Palm Springs’ kind of look with the yuccas — with a shady, minimalist rock garden next to it. It’s traditional Japanese, meets Isamu Noguchi, meets Roberto Burle Marx!” he says with delight, referencing the adventurous, avant-garde Brazilian landscape architect.

The front garden is still a work in progress, say the owners; they’re considering extending the rock garden under the pathway, to the steep slope by the front door. Carmichael is intrigued by the idea.

“In a Japanese garden,” he says, “the gravel would represent water. The stone would be an island, and the house would be a floating pavilion.” He pauses, as the sky slowly darkens and the shadows lengthen, day changing into night as if they were nothing more than two sides of the same thing.

“And the wooden boardwalk,” he says softly, “would be a bridge across the sea.”

— Stephen Brookes, November 2025

Stephen Brookes is the editor of The Hollin Hills Journal. He’s a journalist whose work has been published in The Washington Post, Newsweek, Asia Times, the Chicago Tribune, Architectural Digest, Modernism Magazine and many others.

Photographer Chris McNamara has lived in Hollin Hills since 2001. His photography has been featured in The Washington Post, Modernism and other publications, and he’s also an accomplished portrait photographer.