restoring a masterpiece:

the hollin hills alcoa house

by stephen brookes | photos by tod connell

In 1957, the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) tried to convince people to live in brightly-colored aluminum houses … and failed spectacularly. But as Lee and Peter Braun prove in their stunning restoration of one of the last of Alcoa’s “Care-Free” houses still in existence, the Charles Goodman design was merely ahead of its time — and maybe still is.

welcome to the future!

One bright fall day in 1957, the house of the future arrived on Elba Road. Trucks unloaded 7,500 pounds of aluminum house parts in eye-popping colors: a sky-blue roof, purple exterior walls, a luminous, golden-green front door. More trucks brought acres of cypress and vinyl panelling, as well as bright blue grids for the windows, folding doors in lavender aluminum, electrical outlets that stuck up from the floor and appliances that dropped magically from the walls. And those colors? Forget subtle earth tones or tasteful shades of beige – this house had attitude. And if you thought shimmering teal walls were a step too far, well then … you were definitely in the wrong place.

But the Elba Road house wasn’t some quirky, oddball custom home – it was to be the model for a mass-produced “Care-Free” aluminum home that would take America by storm.

At least, that was the plan of The Aluminum Company of America (now Alcoa), which had hired architect Charles Goodman, the designer of Hollin Hills and perhaps the most innovative architect in the country, to draw up the prototype.

Leave it to Goodman: not only did he incorporate Alcoa products into every nook and cranny, he also made the house both efficient and drop-dead beautiful. About two dozen were built around the country, and the press went gaga. “The most talked-about home in America,” Alcoa promised. “Here is your Dream House made real.”

And then the sizzle turned to … fizzle. Undone by skyrocketing costs, lawsuits, and buyers who found Goodman’s bleeding-edge modernism slightly terrifying, Alcoa abandoned the project. The Elba Road house stood empty for several years, and many of the others fell into oblivion over the decades, either torn down or updated past all recognition; there may only be about a dozen left.

But the ones that survive are extraordinary – and still seem light years ahead of their time.

“When people ask me, I say, ‘well, I live in an eggplant-purple house with blue swirly grids and a lime-green front door, and inside I have lavender and teal walls,’ and they’re like … what???” says Lee Braun, who with her husband Peter bought the Elba Road house in early 2019, and have been meticulously bringing it back to its original technicolor glory. “But the reality is — it’s super cool!”

The Alcoa House dining area, after restoration. Photo by Tod Connell

we’re not in kansas anymore

“Super cool” doesn’t even begin to cover it. From the moment you walk through that shimmering front door, you know you’re not in Kansas anymore. Cypress-clad ceilings soar elegantly overhead, and a vast expanse of glass, framed almost invisibly in aluminum, stretches across the entire front of the house and floods it with light. The living areas are all open-plan, with a family room, dining room and living room horseshoe-ing around a galley kitchen in the front part of the house, while three bedrooms and two original baths line up along the back. And, despite the touches of colored aluminum and vinyl, nothing feels particularly artificial. It’s inviting, sophisticated and full of personality – modernism with a smile.

For the Brauns (both realtors with long ties to Hollin Hills), the restoration has been a labor of love, an opportunity to save a rare and remarkably intact gem of mid-century architecture. At the time they were built, the Alcoa houses were utterly up-to-the-minute, featuring a futuristic GE “work-saver” kitchen, central air conditioning, and synthetic materials that were going to bring about “a new era of Care-free living amid heart-warming beauty.” The original kitchen is gone, alas – the victim of a 1990’s upgrade. But the Elba Road house never changed hands (the son of the original owners still lived there when the Brauns bought it), and remained virtually untouched, retaining most of the original elements that made the Alcoa houses so distinctive.

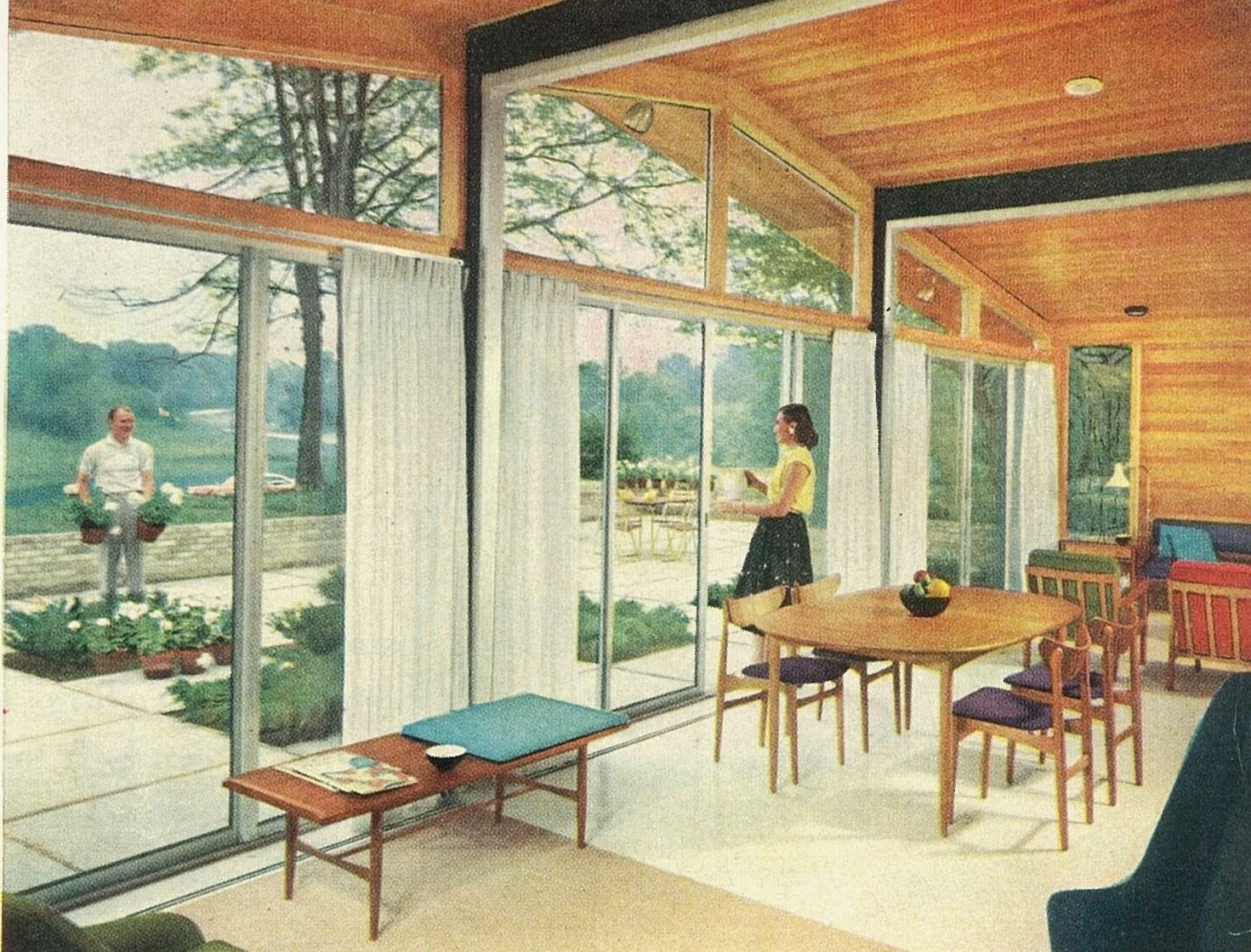

The dining area, from an original brochure c. 1957.

“Everything was in terrible shape — but they didn’t ruin it!” says Lee, who diplomatically describes the house as having been “well-loved.” She and Peter had to correct some key issues – water in the floor ducts, a sag in the roofline, the usual plumbing and wiring headaches – and decided to replace the linoleum floors with polished, heated concrete. They’ve added a new primary bath (because modern plumbing needs no excuse) and will extend the roofline to create a covered patio. Oh, and there’s a new martini bar, naturally.

a meticulous restoration

But for the rest, the renovation of the 1,900-square-foot home has been exceptionally respectful, preserving and restoring as much of the original as possible, while gently pulling it into the 21st Century.

“We’ve had about a hundred conversations about everything,” says Lee. “I’ve never had more conversations about toilets, and sinks, and outlets, and electrical. What do we fight to preserve, and what do we have to let go?”

The family room, with a “storage wall” at right, from an original brochure c. 1957

The entry and family room, after restoration. Photo by Tod Connell

Take, for instance, the electrical-outlets-slash-obvious-tripping-hazards. They’re charmingly quirky – little aluminum blobs that stick up from the floor in unexpected places, like shiny gophers. On the one hand, they’re the coolest outlets you will ever see in your entire life. On the other hand – ow dammit who put that there?

“We only took out two of them,” says Lee. “One was by the door to the outside, where you would stub your toe. And the other was in the middle of the bedroom floor, because ….” Her voice trails off; Goodman’s genius can sometimes be inscrutable. “But we kept the others, and Peter spent over an hour hand-polishing each one, getting off the grime.”

That was just the beginning. The house (which Alcoa once claimed could be kept clean “with a damp cloth”) had to be scrubbed of sixty years’ worth of dirt and, shall we say, patina. The Brauns dismantled virtually every section of the aluminum framing that runs through the house, carefully labelled and cleaned each piece, then finally mitered it all to fit back together, since the new floor was no longer the same height as the old. “It’s been quite the process,” says Lee.

Metallic gopher? Electrical outlet? You decide

Meanwhile, the exterior purple aluminum walls and iconic blue grids were powder-coated to restore their original color, though the interior walnut panelling proved impossible to restore and had to be replaced. The original green and blue kitchen cabinets were taken out of storage and repurposed as a sideboard, and the electrical system turned out to be a hazard (the main panel was located under the kitchen sink) and had to be completely rewired.

The Brauns have taken particular care with the bathrooms, which feature the original periwinkle blue and avocado green laminate walls, one of the original tankless toilets, and hyper-cool scales that fold out of the walls.

“We’re almost 100 percent positive that these are the only two original Alcoa bathrooms left,” says Lee, “and I want them to be ‘show’ bathrooms.”

The floor plan: click to enlarge

Authenticity hasn’t come easy; the decrepit sinks had to be laboriously rebuilt by hand (“these are the most expensive sinks in Hollin Hills, I guarantee it,” she says, drily), old pipes were jackhammered out, and one of the toilets had to be powder-coated to prepare it for polite society.

retro … and beyond

With most of the renovation completed, the couple moved in at the end of September 2020, buying some vintage furniture from the previous owner that had been in the house for decades – including six Eero Saarinen armless dining chairs (cleaned, repaired and re-upholstered in orange Knoll fabric), a pair of Harry Bertoia “Diamond” chairs, a very rare rosewood “Parallel Bar” coffee table by Florence Knoll (which is pictured in the original Alcoa brochure), and a striking modernist oil painting in yellows and reds, which hangs over a vintage stereo cabinet and a stack of Roberta Flack records.

But the retro touches are light, and the Brauns have brought a playful, anything-goes style to the house. There’s a 1960s leather hippopotamus by the front door, and a big pink neon sign in the patio that reads, “Don’t Worry Baby.” Bright splashes of color greet you at every turn, and the house itself gives off a definite California Modern vibe.

“Goodman stretched his design style in new ways with this home,” says Lee. “It really has a Palm Springs feel about it.”

And that may be what makes the house so intriguing. With its walls of glass, low-slope roof, open-plan layout and hug-the-ground profile, it shares plenty of Goodman DNA with the Hollin Hills houses around it. Sure, the purple and gold takes a little getting used to; this is not a self-effacing house by any means. But it doesn’t feel particularly out of place or awkward, either – more like an interesting aluminum foil (sorry) to Goodman’s more organic wood and brick houses.

Given Goodman’s restless creativity, maybe the Alcoa house should be seen not as a quirky anomaly or period piece, but rather a dead-serious attempt to bring mass-produced architecture to the next level. After all, aluminum was reshaping everything else in the 1950’s, from air travel to cars to Christmas trees. Why not housing?

So why did the Alcoa houses fail? Weirdly enough, it turned out that purple aluminum didn’t actually appeal to huge numbers of people. But probably more important was the house’s cost, which Alcoa had badly miscalculated. At a time when a two-bedroom, two-bath house in Hollin Hills sold in the $20,000 range, the Alcoa houses ended up with a price tag of about $60,000 – twice the original estimate, and far out of range for the middle-class buyers they were aimed at.

One of the original Alcoa kitchens

An original Alcoa bedroom

But for the Brauns, there was never any question that the house was a treasure. And as the long renovation winds up, more and more of the home’s neglected beauty is being finally revealed.

“This house makes us so happy,” says Lee, who says it didn’t take the couple long to decide to buy.

“The question that finally did it for us was, ‘would we be upset if someone else bought this house and and ruined how special it is?’ And we looked at each other and said, ‘yeah – we’d be devastated!’”

– Stephen Brookes, December 2020

Peter and Lee Braun. Photo: Albert “Pootie” Ting

Stephen Brookes is the editor of the Hollin Hills Journal. He’s a journalist whose work has been published in The Washington Post, Newsweek, Asia Times, The Chicago Tribune, The Far Eastern Economic Review, Architectural Digest, Modernism Magazine and many others.

Tod Connell is a professional architectural and interiors photographer in Hollin Hills, whose widely-published photographs of Hollin Hills homes have defined the look of the community for many years.

more on alcoa house

Alcoa House dining area and patio, from an original brochure