the handmade, organic furniture of george nakashima found a natural home in the modernist architecture of hollin hills

george nakashima

in hollin hills

by stephen brookes

In 1949, as architect Charles Goodman was developing his bold, innovative architecture across the untouched forests of Hollin Hills, another adventurous young designer was hard at work 150 miles to the north. In a studio deep in the Pennsylvania woods, an architect-turned-woodworker named George Nakashima was hand-crafting a strikingly original new range of furniture, unlike anything anyone had ever seen.

And, just as Goodman’s new houses sought to preserve the forest and connect people with the natural world, Nakashima’s furniture — with its flowing lines, free edges, and spare, sculptural shapes — seemed to celebrate the character and individuality of wood itself. In Nakashima’s words, he sought to integrate “the soul of a tree” into our everyday human lives — and thereby make them better.

“Instead of a long-running and bloody battle with nature to dominate her,” the woodworker wrote, “we can walk in step with a tree to release the joy in her grains, to join with her to realize her potentials, to enhance the environments of man.”

It was a philosophy Goodman would no doubt have shared. And while there’s no indication that the two men ever met, there was such an esthetic affinity between Nakashima’s furniture and Goodman’s light-filled houses that, from the first days of Hollin Hills, its pioneering homeowners made the trek to Nakashima’s workshop in search of his hand-hewed dining tables, grass-seated chairs, walnut cabinets and more — which all seemed to fit with complete naturalness into the modern style of Hollin Hills.

The new furniture “was very popular with Hollin Hills residents” in the early years, write Joseph Rosa and Catherine Hunt in the book, Hollin Hills: Community of Vision. And the community went on to became a virtual showcase for Nakashima in the 1970’s, especially when resident Marjorie Hemmendinger began holding regular exhibits of his work in her Old Town Alexandria gallery. And even now, decades later, dozens of examples — with at least one rather spectacular collection — can still be found across Hollin Hills.

the first collectors

“This furniture goes so well with Hollin Hills houses,” says Bobbie Seligmann, running a hand over the long, sinuous coffee table in her Recard Lane living room that Nakashima made for her in the late 1970’s. “The organic shapes and the geometric architecture play very well off each other.”

George Nakashima • Photo courtesy of George Nakashima Woodworkers

Seligmann’s table is immediately and unmistakably a Nakashima; naturally beautiful and full of character, it feels almost like a living thing. It draws your hand irresistibly toward it; the edges are free and unforced, the lines fluid, the “flaws” in the wood explored and celebrated. The rich grain is sensual, and the parts of the table are joined not with bolts, but with Nakashima’s graceful wooden “butterfly” joints.

It’s a work of art — yet its beauty is quiet and human-scaled, almost timeless. Adorned only with a delicate Japanese red lacquered basket from Seligmann’s collection, it balances with perfect naturalness the modern lines of her home.

The organic lines of Seligmann’s Nakashima coffee table.

Seligmann has lived with her table for almost fifty years — but she was far from the first homeowner to bring Nakashima’s furniture to Hollin Hills. That distinction may go to the pioneering settler Leo Horvath, who bought a home on Recard Lane home in 1952. Horvath had grown up in Pennsylvania, and had known Nakashima when the craftsman was first setting up his studio in New Hope after World War Two.

“Leo Horvath had all of Nakashima’s furniture,” Seligmann says. “A house full of his stuff, before anybody had ever heard of him!”

A page from a 1965 catalog from Nakashima Woodworkers.

the impact of marjorie hemmendinger

While Horvath may have been the first Nakashima collector in Hollin Hills, the most influential was undoubtedly a remarkable woman named Marjorie Hemmendinger. An economist who had worked at the White House, the State Department and the World Bank, Hemmendinger switched careers in 1973, opening the Full Circle Gallery in Old Town, where she specialized in Japanese and contemporary furniture — including Isamu Noguchi's iconic paper “Akari” lamps.

Hemmendinger (an original Hollin Hills settler who passed away in 2020) put together a much-admired collection of Nakashima’s work in her own home on Marthas Road, and soon began featuring his pieces in her gallery, holding one-man shows for the still-little-known designer every year or so for the next fifteen years.

She sold a great deal of his work, and Nakashima would often attend these shows himself, usually in the company of his daughter Mira — now a master furniture maker herself, who runs the Nakashima studio.

“I remember working on many shows for Marjorie Hemmendinger and the Full Circle Gallery,” says Mira Nakashima, now 81, from her home in New Hope.

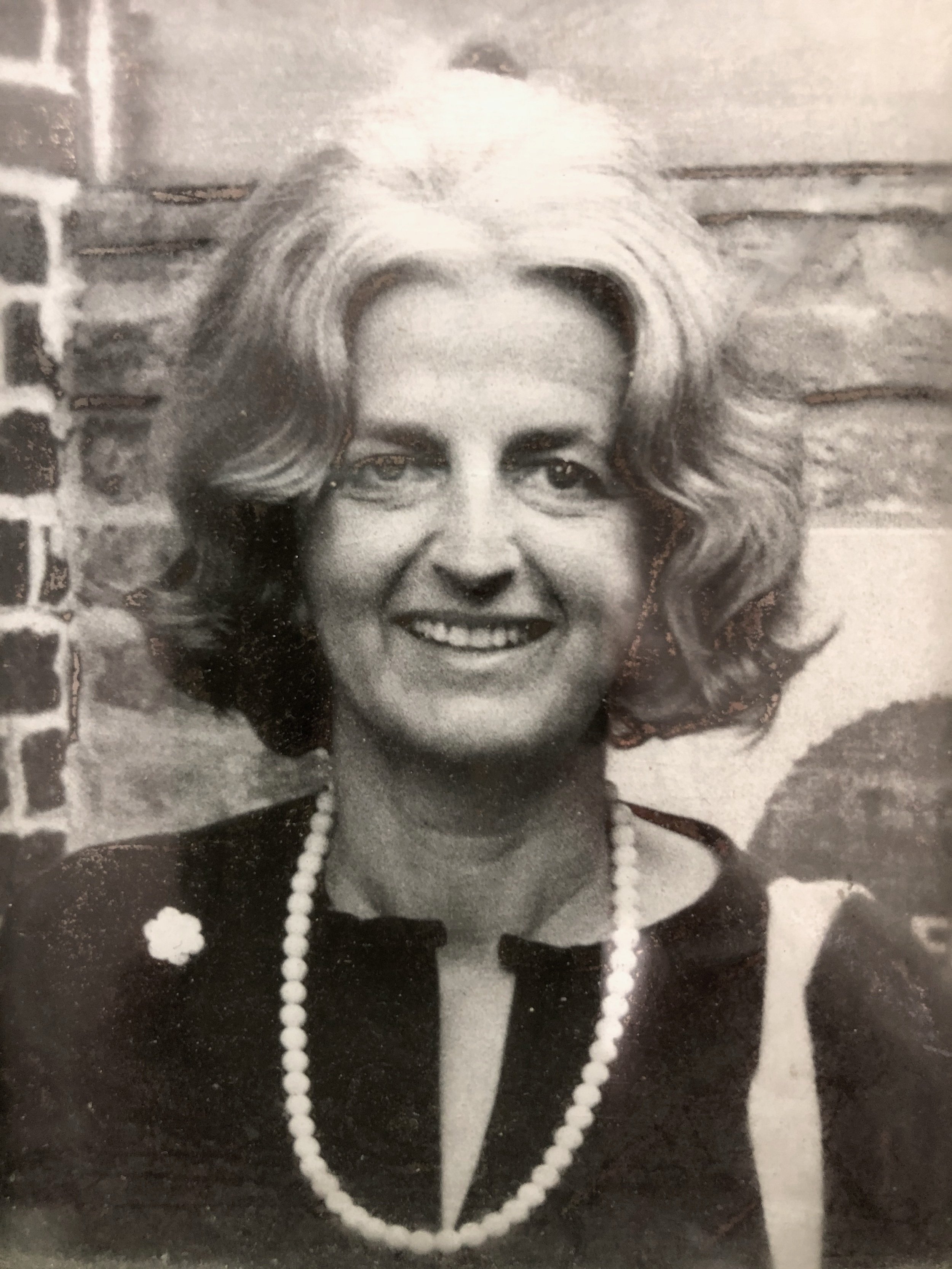

Marjorie Hemmendinger, an important Nakashima collector and owner of the Full Circle Gallery in Old Town in the 1970’s.

“Marjorie would place orders every now and then, Dad would prepare drawings and select wood to make the pieces, ship them, then go down and attend the openings. He would come back pleased, because most of the work was sold out by opening night! We are very grateful to the Hemmendinger family for embracing Nakashima and the Nakashima aesthetic, and for inspiring others to add some to their homes as well.”

the personal connection

It’s not known how many of Nakashima pieces were bought by Hollin Hillers, and Mira Nakashima says she doesn’t specifically recall any individual Hollin Hills clients. But Bobbie Seligmann remembers buying her coffee table at one of the Full Circle Gallery shows in the 1970s, where she met Nakashima.

“He was such a simple, delightful man — he was not commercial at all,” says Seligmann. “He was surprised, I think, to find that there were other people who really liked his stuff!”

That experience of Nakashima seems widespread. When the artist Bobbie Godwin and her husband were house-hunting in the early 1960s, she’d seen a house that had been furnished in Nakashima furniture. She didn’t care much for the house — but she fell in love with the furniture. And when the couple bought their Hollin Hills home in 1964, she insisted on having at least a few Nakashima pieces in their new home.

“We had junk from attics and just scrappy old stuff,” Godwin says, “so I gave my husband no peace until he agreed.” When they finally drove up to the New Hope studio, Nakashima — “a lovely man” — showed them around and helped them select wood. They placed an order for a dining table, a set of chairs, and a charming little three-legged bench.

“They have been wonderful, wonderful things to live with,” she says. “And they cost very little at the time!”

affordability: part of the philosophy

The price factor was key for many Hollin Hillers. Just as Goodman had made it his mission to provide modern, quality houses at affordable cost to young families, Nakashima also kept his prices low, and was much more interested in the quality of his furniture than how much profit he could make. Idealism — and populism — ran deep in the thinking of both men.

A page from a 1965 catalog from Nakashima Woodworkers.

“Even when he was alive, we were working against the modern ethos of technology and mass production and trying to make as much money as possible,” Mira Nakashima said in August 2021, during a tour of the Nakashima studio. “It was more important for him to make something of quality than it was to make something to make a lot of money.”

In 1965, for instance, you could buy a hand-made Nakashima chair for well under $100, or a 60”x 36” walnut dining table for $145. If you were ready to splurge, the most expensive item in that year’s catalog was a stunningly beautiful turned-leg single drop-leaf table, at 72” x 40”, offered at $415. And the workmanship was impeccable; most of the furniture was made in walnut or cherry, but Nakashima kept a wide variety of species on hand, including East Indian rosewood, laurel and teak.

Nothing was mass-produced, and all the pieces required time and a great deal of care to make; the spindles in the chairs were all hand-shaved, for instance, and the furniture was oiled and hand-rubbed to give it a natural surface.

A Nakashima Lounge Chair.

A Nakashima Minguren II coffee table.

Bobbie Seligmann’s free-edge walnut coffee table, designed and built by George Nakashima in the late 1970s. Photo: Stephen Brookes

Moreover, Nakashima felt it was important to involve his clients in the design of their furniture, and his practice was structured around in-person consultations — as Peter and Ginny Kinzler of Stafford Road discovered in 1982, when they visited Nakashima’s studio on the spur of the moment after stumbling across it during a vacation.

Within minutes of arriving, says Kinzler, they were looking through a vast inventory of wooden slabs, settling on a beautiful piece of walnut to be made into a coffee table.

“Nakashima asked us to go home, determine the size we wanted for our living room and send him the dimensions,” he says. Nakashima then drew up sketches, and sent the Kinzlers two designs to chose from, recommending a style called “Minguren I” and noting that the slab was a “fine piece” of wood, “quite thick” with a “rich interesting grain.”

“As he was the master, of course, we chose the table he recommended,” says Kinzler. “When we next traveled to New Hope, we met Nakashima at his studio. On a whim, we asked if he would sign the table. As he went inside his studio to do so, we had visions of him signing it with a hammer and a chisel. Instead, he chose the easier course of a felt-tipped pen. We later discovered that he had not signed his earlier work because he didn’t want to insert his ego.”

And for the Kinzlers, part of the appeal of their table is that it fits in not only with the architecture of their Goodman home, but with their eclectic collection of Asian, Folk, Americana, Shaker, Contemporary and Rustic art and furnishings, as well.

“Above all,” says Kinzler, “Nakashima’s work is art.”

Nakashima’s hand-drawn designs for the Kinzler coffee table.

growing up with nakashima

While there are many examples of Nakashima’s work in homes across Hollin Hills, perhaps the most striking collection belongs to an artist who grew up in a New England home almost entirely furnished with Nakashima’s furniture — and says the experience helped to shape her career.

Her parents’ ultra-modern home (so stylish it was even featured in a newspaper article) was furnished with a wide, custom-built range of Nakashima furniture, from a dining set to coffee tables to lounge chairs , and even specially-designed screens to cover the speakers for the living room music system.

“As a teenager, I thought it was ‘just furniture’,” says the collector (who asked to remain private), sitting at her Nakashima dining table, one of the dozen or so pieces she inherited from her parents. “But as I got older and my taste matured, I realized it was much more than that.”

The pieces she’s lived with for seven decades look utterly at home in her art-filled Hollin Hills home, and include a sideboard, a dining table with a set of grass-seated chairs, two coffee tables and several stools, all of them hand-crafted and strikingly beautiful.

“Nakashima let the wood speak for itself,” she says. “He didn't tamper with the beauty that was already there. What he was trying to do was enhance it, in any way that he could.”

That philosophy, she says, influenced her thinking at a young age. She remembers going with her parents to Nakashima’s workshop when she was in high school, seeing the planks of wood stacked vertically against the walls, and listening to Nakashima talk about the wood and how he would use it.

What made the deepest impression, she says, was watching as the craftsmen put the furniture together by hand, giving the pieces “a kind of natural soul” — an experience that would set her on a career in art.

Not ‘just furniture’: A Nakashima walnut table (with butterfly joint) and grass seat chair, in a Hollin Hills home.

The same pieces in their original home in the 1950’s

Nakashima’s furniture, of course, is famous now, and his original pieces have become collectors’ items that sell for prices that would have seemed astronomical to the early settlers of Hollin Hills. But perhaps the most striking thing about Nakashima’s furniture is that — like Goodman’s architecture — it has aged with extraordinary grace, losing none of its appeal and even growing more beautiful with time.

Perhaps that’s because Nakashima, like Goodman, had little interest in being merely stylish. Instead, both men saw profound beauty in natural forms, and strove for a clean-lined, organic simplicity in their designs. Born only a year apart, and coming into their own simultaneously in the 1950’s, both seemed to embody the idealism, optimism and creative innovation of the postwar world. And, remarkably, Hollin Hills provided a blank canvas where nature, architecture and innovative furnishings could all come together as a whole — and create a setting for an adventurous new generation.

— Stephen Brookes

Interested in learning more? Plan a trip to George Nakashima Woodworkers in New Hope, Pennsylvania, where tours of the fourteen-building complex he built offer insight into Nakashima’s work. Visit the Nakashima Foundation for Peace for more info.

Suggested reading: George Nakashima’s book “The Soul of a Tree” remains the most profound look into the woodworker’s own thinking. “Nature Form & Spirit: The Life and Legacy of George Nakashima,” by his daughter Mira Nakashima is also an invaluable resource.

George Nakashima • Photo courtesy of George Nakashima Woodworkers

A Nakashima walnut table and grass seat chairs, very much at home in Hollin Hills. Photo: Stephen Brookes