what is

mid-century modern?

by michael s. mcgill

photo: yuhan du

How did Charles Goodman come to design the homes in Hollin Hills in what has become known as ‘Mid-Century Modern’ style?

To answer that question, we need to look at three questions. First: what is “modern” architecture? Second: how did World War Two impact housing in the United States? And third: what architectural influences shaped Charles Goodman’s work?

The Birth of the Modern Movement

The Modern movement in architecture stems from dramatic changes that occurred in politics, science, technology, and culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In Europe, the ‘Revolution(s) of 1848’ represented a challenge to nations being led by monarchs, while in America the Civil War is often considered to be the ‘second American Revolution’. The seeds sown by the first American Revolution were growing, both here and abroad, promoting the concept of a broadly defined electorate choosing its own form of government and leaders.

In science and technology, the Industrial Age was in full swing, funding and encouraging a wide variety of inventions and discoveries. Electricity, the telephone and telegraph, extending railroads to link entire continents, elevators, street cars, the automobile, and great advances in medicine and science all combined to speed up the pace of life and make it more challenging and interesting.

These developments induced cultural change. Pablo Picasso in painting, Igor Stravinsky in music, and T.S. Eliot and James Joyce in literature all came to prominence early in the 20th century.

A general attitude was gradually emerging that advances in science and technology could make mankind perfectible in a new age, and that the habits, traditions, and styles of the past were no longer relevant. The horror and savagery of World War One intensified this attitude, adding urgency to finding ways to truly make this conflict ‘the war to end all wars’.

Architect Le Corbusier: a house is a machine for living

In architecture, the Victorian style was coming to an end, with architects rejecting its imitation of past styles such as neo-Gothic, its practice of designing the highly decorative exterior of a building first and adjusting the interior to fit, and its cramped interior spaces filled with bric-a-brac. “Have nothing in your home that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” advised William Morris, and other leaders in the field of design offered similar advice. “Form follows function,” said architect Louis Sullivan. “Ornament is crime,” offered Adolf Loos. “A house is a machine for living,”said Le Corbusier. And architect Mies van der Rohe offered the most concise advice with his dictum, “Less is more.”

Two distinct movements emerged from this dramatic break with the past: Arts & Crafts, and the International Style. They began from entirely different philosophies but gradually over time they began to blend together. They both rejected the architecture of the past.

The Arts & Crafts Style

Arts & Crafts originated in Great Britain, with philosopher John Ruskin as its major theorist. William Morris in England and Gustave Stickley in the United States carried it forward into architecture and interior furnishings in a style Stickley referred to as Craftsman.

Gamble House 1908; photo by Alexander Vertikoff

Rebelling against the Machine Age, the Arts & Crafts movement focused on the value of individually crafted items, the use of natural materials, and simple decorative themes that mimicked nature. The finest example of a Craftsman home in America is the Gamble House in Pasadena, California, designed by the Greene brothers.

While this was a large, luxurious home designed as the winter retreat for one of the founders of Proctor & Gamble, the style also resulted in the widespread development of small, affordable bungalows, with wood exteriors, low pitched roofs, large porches and gables on the outside, and large public rooms combining living and dining rooms, libraries and music rooms on the inside. Sears, Roebuck even offered a Craftsman kit house in its mail order catalogue.

One of the foremost practitioners of this style, at least early in his career, was Frank Lloyd Wright, whose Prairie Houses in the Midwest demonstrated his own brilliant adaptations of the Arts & Crafts movement.

The International Style

The International Style represented a much more revolutionary break with the past. It embraced the Machine Age, promoting the use of innovations in manufacturing to create austere rectangular boxes made of metal and stucco, with large walls of windows, the absence of any decoration whatsoever, and flat roofs.

Many of the foremost practitioners of this style in the United States were Europeans who were initially inspired by the designs of Frank Lloyd Wright, but gravitated to the more bold departures from the past designed by Le Corbusier in France and the Bauhaus in Germany. These architects came to America in some cases to work with Wright, but also to escape the economic hardships following World War One and the depredations of Nazi Germany leading up to World War Two.

Among the foremost pioneers of the International Style in the United States, Richard Neutra excelled in residential design, while Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer were among the leaders in a wide variety of building types.

These two distinct styles of architecture blended together and combined with the dramatic changes that occurred as a result of World War Two to usher in Mid Century Modernism. Architect Charles Goodman drew upon each of these styles to design the distinctive homes in Hollin Hills.

Villa Savoye, Poissy, France (Le Corbusier, 1931)

The Impact of World War Two on Housing in America

World War Two brought enormous changes to the United States. Before the War America remained mired in the Great Depression, with high unemployment, little private sector construction, and a weak consumer economy. What would happen when the War came to an end? Would a depression return?

Just the opposite occurred. The enormous pent-up demand generated economic growth, which provided consumers with jobs and a salary that allowed them to make up for more than a decade of buying very little other than the necessities of life. Technological innovations developed for the War also boosted the economy, with lower cost production, greater standardization in manufacturing, and the invention of new consumer goods all contributing to this process.

Passage of the G.I. Bill of Rights further fueled the economy, enabling veterans to finance the purchase of housing. Demand for housing skyrocketed, and the industry had to develop new methods of construction, with new materials developed during the War, to meet that demand.

More widespread ownership of private automobiles, federal financing guidelines that favored new housing over existing stock, federal construction of highways, and the availability of less expensive land resulted in much of the new housing development occurring in suburban locations. These homes could be equipped with more conveniences than before the War, including the all-electric kitchen, televisions, and furniture made with the plywood and plastics developed or improved because of the war effort.

These trends coalesced into the development of subdivisions like Hollin Hills. But there was no consensus throughout the nation regarding the design of this new housing. How, then, did the style of housing in subdivisions like Hollin Hills emerge?

Another impact of the War was the growth and development of the emerging Sun Belt, as the federal government located factories for war production in this part of the country. No place benefited from this trend more than California, and particularly Southern California. It was here that a vigorous campaign was launched to promote new housing designed in the International Style, which by this time had come to dominate the Modern movement in architecture.

The Case Study Houses

In 1945, John Entenza, the publisher of Arts & Architecture magazine, commenced the Case Study House program in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. His goal was to develop a series of International Style houses that could serve as prototypes for meeting the burgeoning housing demand following the War. From 1945 to 1966, the magazine published 34 designs for such housing, of which 26 were built.

Entenza invited specific Southern California architects to design affordable, replicable houses. They were to have wood or metal frame construction without load-bearing walls, thereby facilitating open interior spaces and large window walls to emphasize the indoor/outdoor character that showcased the wonderful climatic conditions in Southern California. They were to exhibit a minimum of ornamentation and a streamlined rectilinear geometry.

Given the emphasis on ‘form follows function’, modernists felt there was no reason for steep roofs, which enclosed fairly useless space. So, Entenza specified flat or low-pitched roofs, thereby encouraging the observer to focus on the main body of the house, where the ‘functions’ were contained, rather than its roof.

To enhance the affordability of these homes, Entenza encouraged modular construction, the use of readily available standardized fixtures, and he sought major manufacturers of housing components to donate some of their products with the promise that the program would publicize them.

By this time, Los Angeles had emerged as the center for International Style housing design in the entire country, so there was a large pool of talented architects on which to draw. The designs they produced are in many cases spectacular, one of the most famous being House #22 by Pierre Koenig, a home cantilevered out over a hillside, with the L.A. skyline in the distance. Photographer Julius Shulman, who began his career early in the Case Study House program, produced a stunning photo of the home at night, standing outside looking through the glass wall of windows at the brightly lighted interior while downtown L.A. sparkles in the distance.

Most of the Case Study homes did not pursue the use of dramatically different construction materials and techniques, although Charles and Ray Eames did so, using industrial building components.

None of the homes was very affordable or replicable, instead serving as custom designed houses for financially secure clients. Nevertheless, the Case Study House program offered a dramatic, widely publicized promotion for International Style housing.

Charles and Ray Eames House, Pacific Palisades, CA (1949)

While a few merchant builders would take the bait dangled by John Entenza, including Joseph Eichler in California who went on to build more than 11,000 homes in both Northern and Southern California, and, on a much smaller scale, Robert Davenport in Hollin Hills, most merchant builders opted instead for more traditional designs which they produced by the tens of thousands in such cookie-cutter subdivisions as the various Levittowns.

The Case Study House and its progeny eventually came to be known as being part of the ‘Mid-Century Modern’ style. The style really reflected the evolution of Modern architecture over the first half of the 20th century, suddenly becoming much more prevalent because of the post-War housing boom that occurred at mid-century. As can be seen in the work of Charles Goodman in Hollin Hills and elsewhere, few of these homes reflected the absolute purity of the International Style. Instead, they incorporated a variety of design influences. They also evolved over time into less original examples of Modern architecture, such as the ranch style house.

But one can nevertheless marvel at the dedication, ingenuity, and bold vision of people like John Entenza way back in 1945, as they sought to remake America through the dissemination of a dramatic new approach to residential architecture. They are now, long after most of them have died, finally achieving public acclaim for the movement they spawned: Mid-Century Modern.

The Architect Charles Goodman

Modern architecture began late in the 19th century, branching into two distinct schools—first, the more romantic, nature-oriented Arts & Crafts movement, including Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie Style homes; and then, a decade or so later, the more rational, technology-based International Style. These styles were distinct, but they borrowed from one another over time. Elements from both appear in Hollin Hills, based on the work of architect Charles Goodman.

How did Charles Goodman develop his approach to architecture? Born in New York in 1906, Goodman grew up in suburban Chicago and studied at the Armour Institute, graduating in the early 1930s. Chicago was one of the most dynamic, experimental centers of architecture in the world, where the high rise office building was invented after the Civil War and dozens of Prairie Style houses were designed by Frank Lloyd Wright early in the 20th century.

The Armour Institute, like most schools of architecture, initially ignored the Modern movement. It was not until after Goodman left that Mies van der Rohe moved to Chicago to merge Armour and another school into the Illinois Institute of Technology and switch to a modernist curriculum. Nevertheless, the ‘International Style’, coined by Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson to describe the works of modern architecture they exhibited in 1932 at the New York Museum of Modern Art, was all the rage among young architects.

So, it can be assumed that Charles Goodman absorbed the work of Frank Lloyd Wright by living in the Chicago area, and became familiar with the International Style early in his architectural career.

The new approach to design in the Modern era was aptly summarized by Frank Lloyd Wright: “the reality of the building is the space within to be lived in, not the walls and ceiling.” His Prairie Style homes still accommodated servants, so the kitchen remained in the back of the house. More affordable International Style homes, bereft of servants, including those in Hollin Hills, pushed the kitchen forward to be more closely linked to the large open public area that both styles emphasized. Bedroom areas remained private.

With regard to the relationship of a house to its site, Wright said “Let your home appear to grow easily from its site and shape it to sympathize with the surroundings if nature is manifest there, and if not, try and be as quiet, substantial and organic as she would have been if she had the chance.”

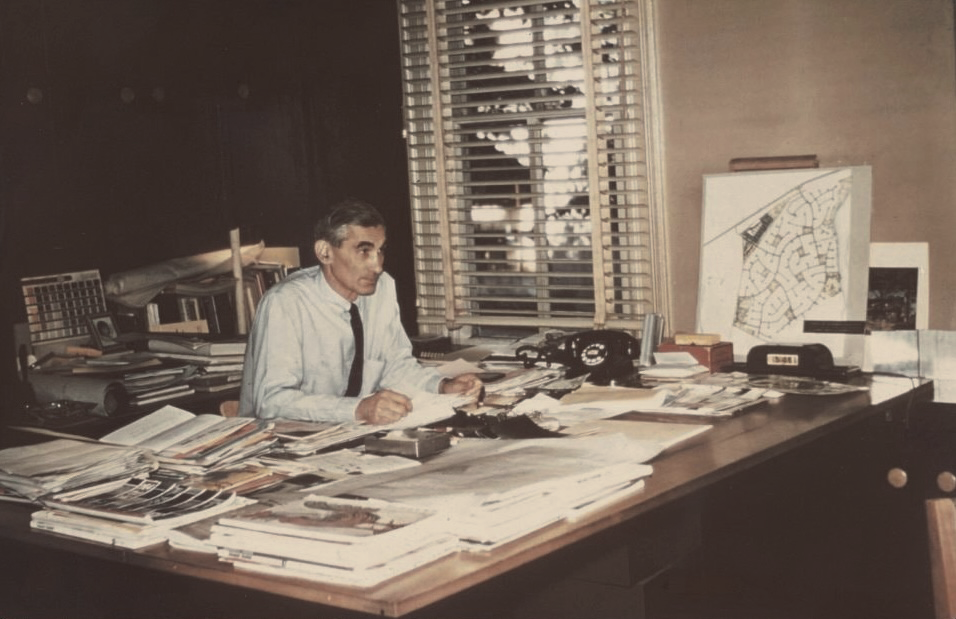

Architect Charles M. Goodman

Charles Goodman enhanced the natural environment in Hollin Hills by minimizing grading, preserving mature trees, orienting each home to have a private view out the front, and a sense of a common green in back as the yards blended together. He and Robert Davenport even provided homeowners with an individualized landscape design that enhanced the outside world even further. So, Hollin Hills made the outdoors a welcome extension of the interior, rather than having a flat, denuded landscape full of identical homes sitting cheek by jowl. By way of contrast, International Style homes sat on top or even above the landscape, on stilts, termed ‘pilotis’.

Prairie Style homes were made asymmetrical by arranging rooms in a cross or pinwheel pattern and included exterior decoration, such as leaded glass windows depicting abstract interpretations of flowers and the inclusion of large, built-in urns. Goodman embraced the International Style emphasis on asymmetrical homes that were square or rectangular, with a minimum of decoration, even going so far as to design large windows with the most minimalist of frames.

A comparison of the characteristics of Goodman’s low-pitched-roof homes and his flat-roof homes illustrates a tendency on his part over time to move closer to the International Style. The publicity garnered by the Case Study House program in Southern California doubtless reinforced this tendency. Indeed, even Frank Lloyd Wright did this with his Usonian House design, begun in the late 1930s, featuring affordable, usually single story homes, with flat roofs, vertical wood siding, modular construction, and window walls opening onto a landscaped back yard. This was by no means Wright’s only product during this period, prolific and creative as he was, designing such extravaganzas as Fallingwater near Pittsburg, and Wingspread in Racine, WI.

An early Charles Goodman design in Hollin Hills. Photo Robert C. Lautman, National Building Museum

Diehard International Style architects including Richard Neutra and Marcel Breuer were just as willing to deviate from the style’s orthodoxy, responding to the desires and incomes of specific clients, building in different geographic and climatic zones, and utilizing a wider variety of materials. But certain core principles remained—design from the inside out, minimize ornamentation, create a streamlined and clearly articulated asymmetrical geometry, unify the inside and outside worlds, retain flat or low-pitched roofs.

It was Charles Goodman’s achievement, with Robert Davenport, to take his own variant of the modernist style and create a living, breathing neighborhood that still flourishes after more than seven decades, accommodating additions to the original homes but retaining its Mid-Century Modern character so well as to qualify for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

— Michael McGill