in hollin hills, a HIRO of modern art confronts a dark history

by stephen brookes

From a WWII internment camp to the Smithsonian, a Marthas Road artist has left a searing mark on the world

Before inviting you into her studio on Marthas Road, the artist HIRO (one name only please, and all caps) has a quick, tongue-in-cheek warning. “You’re not claustrophobic, are you?” she asks, with an impish grin. “Because … it’s a little crowded in here.”

Crowded? It looks like an avalanche of art just roared through. There are paintings stretched across every wall – brightly colored cityscapes, huge expanses of calligraphy, delicate drawings and intricate collages. Paintbrushes and reams of handmade paper cover her work tables, along with stacks of gallery announcements and reviews of her work. There are bulging Rolodexes and piles of letters, and the shelves are packed with books on everything from Alexander Calder to Japanese history. And much of the furniture – including a piano – has been repurposed as work space, heaped with photographs and documents for a planned autobiography.

It’s a wildly creative space that reflects an equally creative artist – one as committed to social justice as to art itself. And the key to her art may be a collage that hangs high on one wall, a striking work with expressive, almost yearning brushstrokes on torn Japanese paper, trapped under snake-like twists of barbed wire and rope.

From the series, ‘Kimono and Barbed Wire’

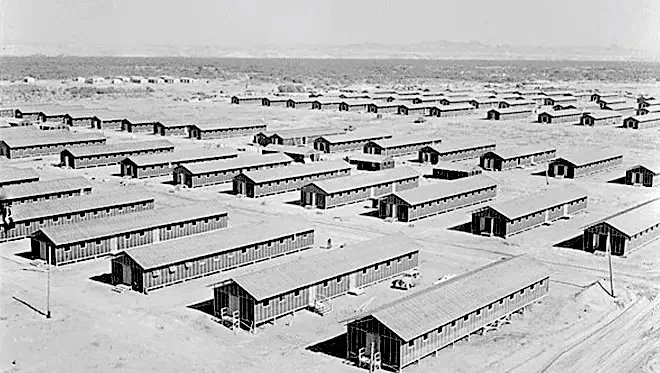

“That’s from my series ‘Kimono and Barbed Wire,’” says HIRO, a petite but forceful woman who still (at an age she won’t divulge, so let’s just call it “timeless”) continues to work. The piece grew, she says, from her years of imprisonment as a child in the Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona – one of the ten internment camps for Japanese-Americans set up during World War Two, when 120,000 innocent people were incarcerated.

“Brushstrokes”

A Japanese-American internment camp in Arizona

“I wanted to show the pain of that experience,” she says. “My family lost everything. We were put behind bars.”

It was a harsh introduction to prejudice – and it shaped the course of HIRO’s life. In Chicago after the war, as the valedictorian of her high school, she spoke about it and was met with stony silence. But the die was cast.

“There was a political element in my thinking from the very beginning,” she says. “I felt that I was a victim of these things, and I was going to do something about it. I thought, if I’m going to be an artist, I have to know about my society.”

She went on to study chemistry and politics at the University of Illinois, before getting a Master’s degree in International Relations with a focus on Japanese politics. Then, still largely self-taught as an artist, she moved to New York to study painting more formally at Columbia University, and embarked on a series of lively, vividly-colored cityscapes titled “City Lights.” But she also began putting her political ideas in motion by promoting other Asian-American artists, setting up exhibits and speaking engagements for them in New York and Washington, DC.

Windy Brushstrokes

HIRO at the Smithsonian

It was the beginning of a wide-ranging career that would take her all over the world, using art to focus attention on civil rights, feminism and, above all, better understanding between East and West. After moving to DC in 1981 (and Hollin Hills in 1996), she became a ubiquitous figure in the art scene here, exhibiting the first of her “Kimono and Barbed Wire” works at the Smithsonian Institution and giving talks at the National Portrait Gallery, the Cosmos Club and other venues. She took on a range of new roles – curator, editor, board member, speaker, teacher – for organizations including the Washington Women’s Art Center, the Japanese American Citizens League, the D.C. Humanities Council and many more.

HIRO at the Smithsonian FolkLife Festival in 2010

“There was a political element in my thinking from the very beginning”

And in her own art, she began exploring feminist issues, using gestural brushstrokes in an almost calligraphic style in such works as “Signet Woman” (1986) which became the cover of an important Japanese book on feminism. She expanded into performance art, joining the D.C. Chapter of the Women's Caucus For Art where she presented "Ring of Fire" – in which she made (then ritualistically burnt) a new painting. And her series of “Free Spirit” paintings, with their universal themes of justice, hope and friendship, remain some of her most abstract yet joyful work.

The list of HIRO’s exhibits, performances and lectures seems almost endless, and her work has had an undeniable impact: two major paintings (“Sada Memories, Thoughts on Justice,” and “Justice For All”), for instance, were part of an exhibit on “Japanese-Americans and the United States Constitution” that ran from 1987 to 2005 at the Smithsonian’s American History Museum.

Her large “Kimono and Barbed Wire” murals have been seen all over the world, as part of performances she’s put on in museums, embassies and universities. She’s taught and lectured extensively at the Smithsonian, and thousands more people experienced her work at the Smithsonian’s 2010 Folk Life Festival on the Mall, where she painted a 24-foot-wide “Kimono” mural in live performance.

And at the core of virtually everything she’s done has been her own seminal encounter with injustice, which gives her art the ring of authenticity and purpose.

“Why should I do something that is not part of my experience?” she asks. “I can rely on the rich experience I have, and use it. And that’s exactly what I did.”

— Stephen Brookes, December 2020

Signet Women, 1986